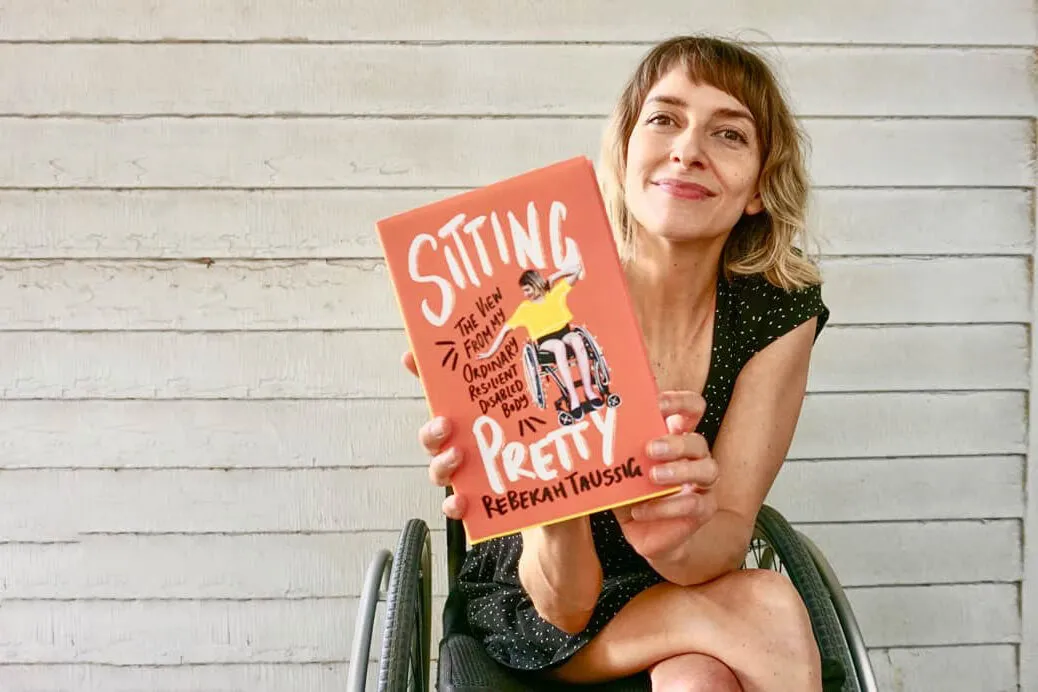

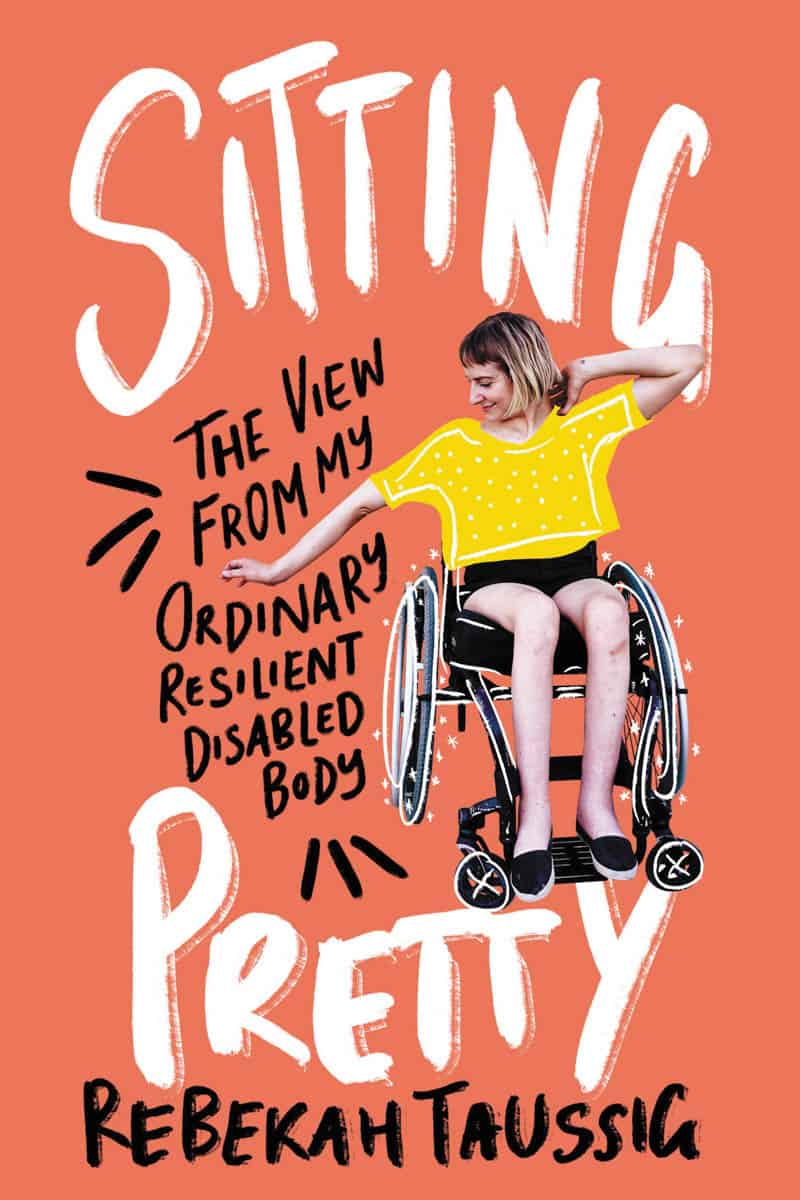

Sitting Pretty

The View From My Ordinarily Resilient Disabled Body by Rebekah Taussig

‘We should bring disabled perspectives to the center because these perspectives create a world that is more imaginative, more flexible, more sustainable, more dynamic and vibrant for everyone who lives in a body.’

Disability, Taussig points out, is an inevitable part of aging. And yet, in calls for greater diversity and inclusion, disability is frequently forgotten or mentioned last. Taussig experienced this herself when she went to an anti-Trump march in January 2017. On her poster, she wrote, “Women’s Rights, Disability Rights, HUMAN RIGHTS”. Whilst she was surrounded by messages from Climate Change to Black Lives Matter, she did not see any other posters about disability or any other women using mobility aids; though she notes that may have been partly down to the inaccessibility of the event. I can argue that you should care about disability rights as you do other issues, even those that do not directly affect you. But if you still can’t find it in your heart to care – if you need a selfish reason to care – then let it be that you have a body. And no body is infallible.

Sitting Pretty is told quite literally from the point of view of Taussig’s ordinarily resilient disabled body. It is a lens with which she shares her thoughts and experiences on accessibility, desirability, ableism, kindness, feminism, and more. Although Taussig has a PHD, the book relies on story-telling to share academic ideas, making it an incredibly accessible read.

The violent chemotherapy and radiation used to treat Taussig’s cancer left her paralysed by three years old. As a child, Taussig did not see her disability as worth factoring into her self-evaluation. When she became disabled, her parents did not install ramps or handrails. The youngest of six, she still slept on the top bunk of the top floor of the house. She crawled alongside her brothers and sisters. However, the older she became, the more she started to realise her differences from other people. And she was particularly troubled by the extra help she needed.

‘I calculated that people spending time with me cost them something extra, and I wanted to spare them that high price. Starting around the age of eight, I cut friends out of my life as soon as I sensed my presence cost any extra strain.’

These negative feelings were amplified when she saw a photograph of herself, and realised that the body she imagined herself having was not like the body she possessed.

‘I started to crop my lower half out of every image. If I never saw it, I could pretend it didn’t exist.’

As someone with a disability, I am also guilty of curating photographs so that my disabled limbs are not visible. And what I relate to so strongly in Taussig’s writing, and what might surprise nondisabled people, is that it does not start off this way. We are not born hating our bodies, none of us are. It is through socialisation that we grow to hate them. It is through socialisation that we are fed messages that our bodies are lesser than. And this is especially true for disabled people.

‘I consumed and digested the culture around me and slowly learned, with certainty, that I was not among those who would be needed, admired, wanted, loved, dated, or married.’

This ties into Taussig’s difficult-to-read section on her first marriage. When she was twenty-two, she married a man that she did not love, because she thought that no body else would ever want her. Everyone told her how lucky she was to be loved by him. On her wedding day, Taussig was determined to walk down the aisle. She reflects on how she did this because disability is seen as something that needs to be overcome. Not only this, but because disability and desirability are not known to co-exist. After a short-lived marriage, Taussig met her new partner. This time, she was more at peace with her body, and so, her wheelchair was not cast aside.

‘My chair was part off all the photos, an extension of me, a part of our romance.’

As a disabled woman, I relate to much of what Taussig writes about feeling that romance would not be part of my story, and settling for ill-advised matches because I believed that no one else would want me. The self-acceptance that ends Taussig’s section on romance is palpable, and very, very necessary.

Taussig explains the medical and social model of disability. The medical model essentially says that people are disabled by their impairments and differences. The person is at fault. The social model argues that people are disabled by the world being inaccessible, rather than by their impairments. Taussig illustrates this with a woman in a wheelchair at the bottom of a staircase. The medical model would say that the woman’s legs and their inability to walk are the problem. The social model says that it is the fault of the building for not having a lift. Nondisabled people seem not to understand that the main strain does not come from the impairment but from the external attitudes towards it.

‘these legs of mine are not The Most Debilitating Problem. At least, not in the way outsiders expect. When I look back and evaluate the most limiting, painful parts of my life, or even, more specifically, the hardest parts about being disabled, it’s not just my legs. It’s stigma, isolation, erasure, misunderstanding, scepticism, and ubiquitous inaccessibility. And that part – right there – is the social model understanding of what it is like to live in an ableist world when you’re disabled. Despite all that, my paralyzed legs are the only thing outsiders seem to see.’

Every time I try to pick a favourite chapter, I feel that I’m betraying another. But the chapter entitled, ‘The Complications of Kindness’ is the most essential read. It is an especially essential read for anyone who thinks that they understand disability and know how to treat disabled people. Using examples from her life, Taussig delves into times when well-intentioned people have stepped in to help her, and in doing so, have caused her pain and frustration.

In one instance, a woman prays for Taussig to be cured, even after being expressly told not to. At a function raising money for disabled children, the nondisabled children dance and the disabled children are passive props to their dance. In another scene, after Taussig says that she does not need his help, a man refuses to stop watching as she gets into her car.

‘I know it looks like I don’t, but really, I’ve got this’

This chapter is particularly pertinent as, so many times in my life, I have been told to remember that a nondisabled person is, ‘only trying to be kind’. In this way of thinking, the wants of the disabled person are erased. They become the recipient, willing or unwilling, of a nondisabled person’s kindness. It can be infuriating. Nondisabled people often do not understand that through a lifetime of adaption, we really have got this.

Sitting Pretty is one of the most articulate reads on disability. There is so much that I have not mentioned here, including how expensive it is to be disabled in America and the perils of trying to find accessible housing. Crucially, when we grapple with disability, we grabble with the body. And when we grapple with the body, we are faced with its complexities, its fragilities, its endurance, and so much more.