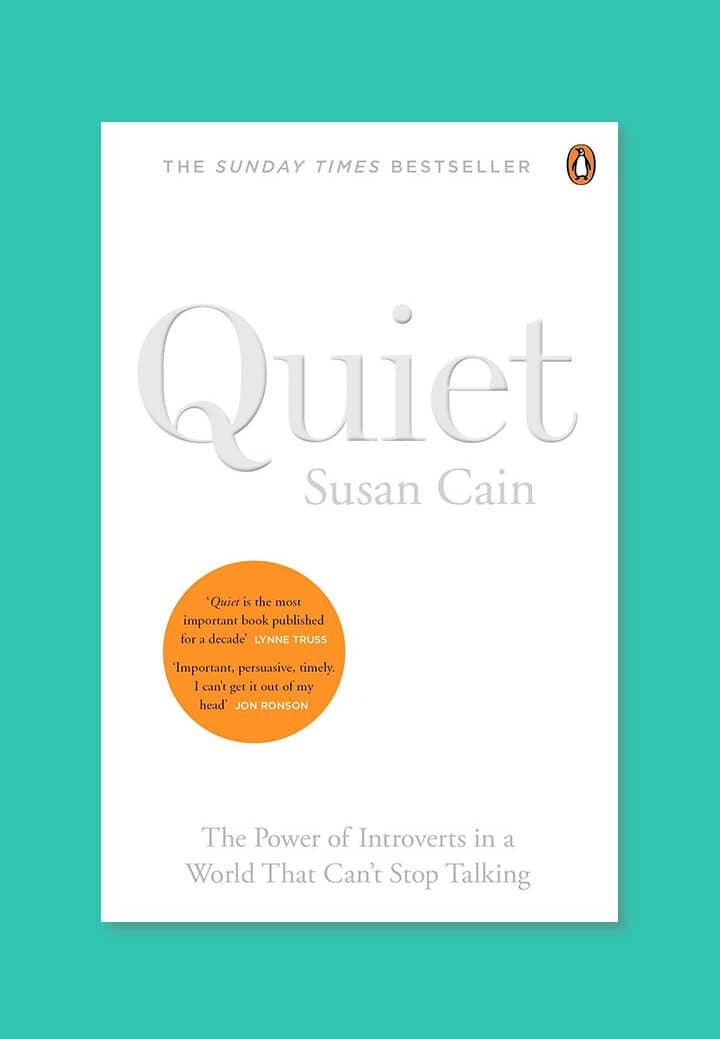

Quiet

I was about thirteen when I first read Quiet. Back then, I fantasised about outgrowing my introversion. One day, I won’t find small talk awkward. One day, I’ll prefer going out to staying in. One day, I’ll have lots of friends rather than a cherished few. I felt a societal pressure to not be introverted. Being introverted felt like being in the wrong. It felt like a character flaw to be challenged, altered. But Quiet gave me peace. The peace to be introverted without self-criticism.

You probably immediately self-identify with being either an introvert or an extrovert. According to different research, one third to one half of us are introverts. In the introduction, Cain offers a checklist of qualities that indicate you are an introvert: I prefer one-to-one conversations to group activities; I often prefer to express myself in writing; I do my best work on my own, and more. If you say ‘true’ to the majority of the checklist, then you are probably an introvert. If your answers are ‘false’, then you are an extrovert.

‘Our lives are shaped as profoundly by personality as by gender or race.’

Quiet is hard to define. It is a compilation of story-telling, history, research (both sociology and psychology) and lived experience. There are moments of relatability, ‘many have a horror of small talk, but enjoy deep discussions’ and ‘(Taking shelter in bathrooms is a surprisingly common phenomenon, as you probably know if you’re an introvert…)’. Overall, what Quiet does, is acknowledge and validate introverts. Throughout it holds true to one point: it is not a bad thing to be an introvert. Being an introvert is just different from being an extrovert. The explanation for why introverts might feel this way comes in the prominence of the Extrovert Ideal.

‘the Extrovert Ideal – the omnipresent belief that the ideal self is gregarious, alpha, and comfortable in the spotlight.’

‘Extroversion is an enormously appealing personality style, but we’ve turned it into an oppressive standard to which most of us feel we must conform.’

The Extrovert Ideal is first established at school. My school had a mantra about creating ‘well-rounded individuals’. Being the nerdy type that is unequivocally brilliant at one or two subjects was not what they wanted. You were meant to get involved with everything: it was good for you to get involved in everything. This meant being on the sports team, being average or slightly above average at every subject, auditioning for drama, being friends with everyone. This felt exhausting.

The environment we were meant to be educated in exhausted me too. Introverts need alone time to recharge. But school has a strong focus on group work, grouped tables, and constant class participation. In group work, the words of a quiet child are often disregarded because they were not the loudest or the first to speak. I recollect how, after group work, when the teacher then called out the right answers, I would hear my answer – the answer that no one had listened to – was correct. Quiet reassures us: there is no correlation between intelligence and speaking first or the loudest.

Teachers and parents often worry how a child is going to function in the world, if they cannot live up to the Extrovert Ideal. Cain addresses this by tackling the assumption that introverts cannot possibly be leaders. Research shows introverts make effective leaders. As they are actually more inclined to listen to their subordinates, as they are not as concerned with dominating a room as extroverts are. Indeed, Cain offers examples of introverted leaders. Her story-telling style gives shape to the quiet but powerful lives of Moses, Stephen Wozinak, and more.

Cain also talks about perfect pairings of introverts and extroverts throughout history, and describes the symbiotic relationship as being like East and West, masculine and feminine. Rosa Parks’ quiet stoicism was a good companion to Martin Luther King’s outspokenness. Eleanor Roosevelt had the thoughtfulness that paired her well with her husband’s confidence.

Quiet stresses the importance of Deliberate Practice, something introverts are prone to doing. This is when you go away and focus on your passions alone. Be that computer programming, gardening, or creative writing. It is during Deliberate Practice that you really fine-tune your skills, because you are focused on what is challenging to you, not to other people.

‘it’s not that I’m so smart,” said Einstein, who was a consummate introvert. “it’s that I stay with problems longer.’

Even if you are comfortable in your introversion, there can still be moments where you might wish that you could be more extroverted. Perhaps you need to do a speech, attend a party, chair a conference. Quiet delves into the pseudo-extrovert. Pseudo-extroverts are introverts who can imitate extroverts enough to be perceived as extroverts. Cain writes that introverts are most equipped at doing this when it comes in service of doing something they care about. For example, they might dread public speaking with every fibre of their being but they need to give a talk on environmentalism, and they are really passionate about environmentalism. It is for this purpose that they are able to appropriate extrovert traits and make their speech. Cain argues that in order to be a pseudo-extrovert, you need to recuperate by nourishing your introverted self. So, after giving the speech, you might spend the rest of the day watching television alone. You can appropriate extroverted traits as long as you look after your introverted self.

‘The truth is that many schools are designed for extroverts.’

At the end of the book, Cain offers tips for how to parent an introverted child, especially if you are an extrovert and are having a hard time understanding your child. The key, which Cain reiterates over and over again, is not to perceive introversion as a bad thing or something that needs changing. It is okay for your child not to want playdates after school. It is okay for your child to nurture a few friendships, rather than many. It is okay for your child to want downtime.

Furthermore, Cain points out that often, when an introvert blossoms after school, we assume that they have outgrown their introversion. What has really happened is that we have more choices as adults. We choose our careers, our friends, our spouses, our environments…we make our introverted selves comfortable enough to blossom.

‘Don’t think of introversion as something that needs to be cured.’

On the front and back cover, on the opening pages, there’s praise for Quiet. Jon Ronson, Harvard Business School, the New York Post. But the standout word is from Lynne Truss, ‘important’. Quiet is an important read. It is an important read for thirteen-year-old girls who feel their introversion makes them inadequate. It is an important read for extroverted parents who can’t comprehend the seemingly strange ways of their introverted children. But it is also an important read for the world at large. It is important because it not only validates the experience of introversion – more than that, it addresses the power of introversion.